The Holy Cephalophore - Commentary

I feel sometimes Explaining The Comic kind of tends to be a bit corny, since I like for people to generally have their own takeaways from what I make on their own. However I did make this in some interesting circumstances, and I think it would be fun to share my thoughts for those who were curious.

First of all, as mentioned in the bonus comic, this is the very first full comic I've made that is completely drawn traditionally, pen on paper. Most major edits and changes as well were done directly on paper with deleter white. The first few pages were done with micron pen, and later I switched to doing all the pages with a Pentel brush pen. The lettering as well was done with micron except for the opening illumination-style page and the pages with Philip at the French court.

It's also the first comic I've done after finishing my schooling and finally having free time again, so I was kind of in a frenzy to make something with my hands again and throw myself into creativity after a couple years of being very busy.

I initially wanted to do this as part of a larger story I had in mind that connects this with my original Devilsburger story I’ve been working on, which is basically kind of taking these historical figures and placing them in a modern setting, with rough parallels to real personalities and events. I did post some pages of the original comic I was making on my blog which I’ve tentatively titled ”Goodbye Richard!” . It’s TBD if I’ll get around to finishing that story, but I did enjoy making the parts that I did and am glad for the positive reception of it.

However, when creating this I thought I would simply focus on the historical story as to not get *too* tangled up with other OC lore and other complicated context-dependent stuff. I did end up doing some more research about the central event–the death of Richard the Lionheart–and it was very interesting to delve into the myths and facts of it all. I wanted to make this bonus section to sort of organize some of the things I learned that may be of interest, both to people unfamiliar with the historical references as well as to enthusiasts.

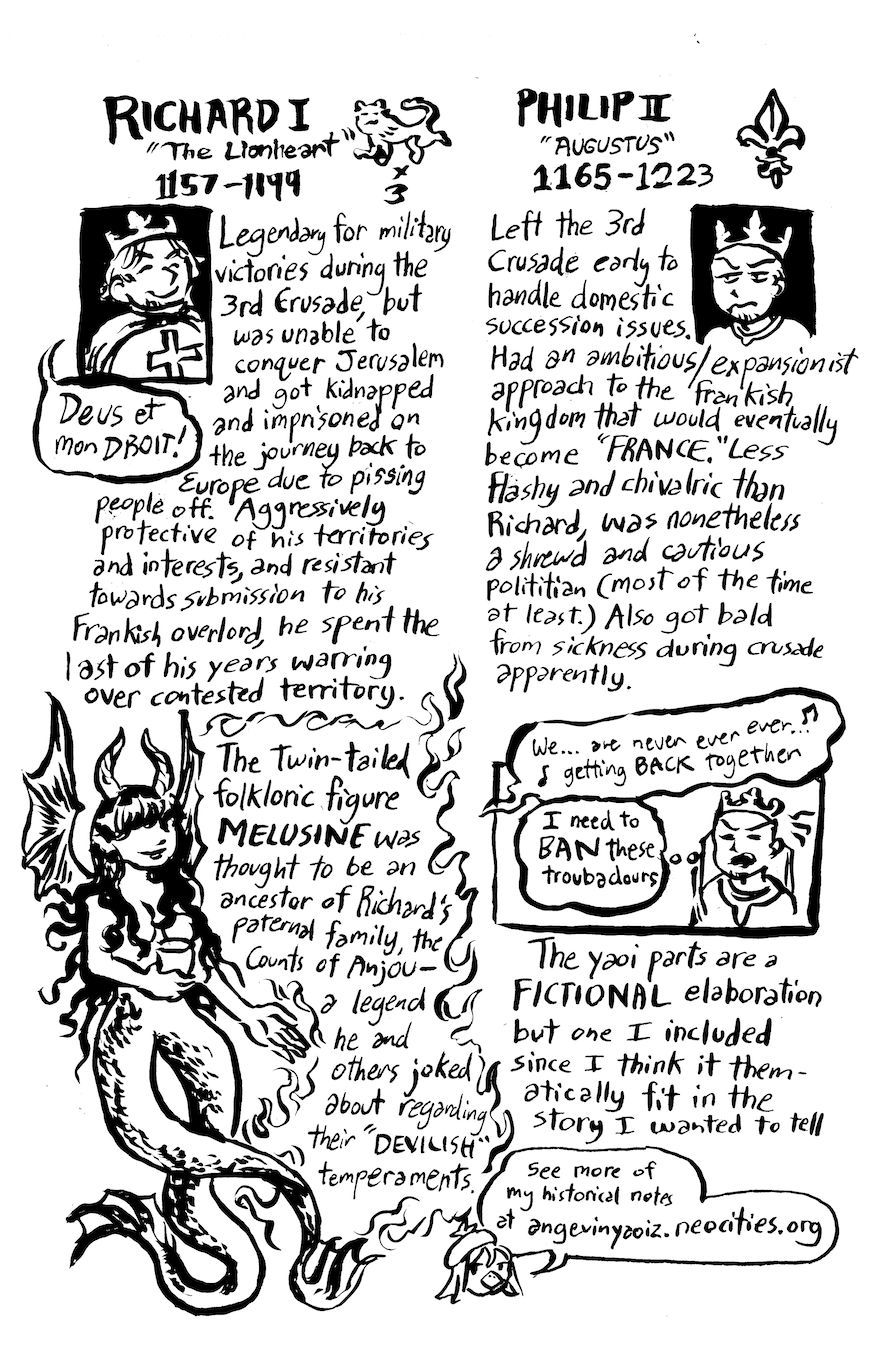

Historical Contexts

The story of the death of Richard the Lionheart usually ends up being a moralistic tale about a strong warrior brought down by greed and power-lust. If the authors are feeling redemptive towards him, they usually also include the story of Richard forgiving his killer, but it is always with a tinge of the dramatic. I was interested in this story because I feel the popular media depictions of his death seem to follow this moralizing tale, and pick and choose which elements to include. In the 1976 Robin and Marian, Richard is shot while besieging and burning a castle of innocent people while demanding treasure. In the 2010 Robin Hood, He similarly is shot down after being portrayed as a greedy warmongerer. Both cinematic portrayals have him killed in combat, while wearing his iconic knightly chainmail, which is odd because to me the outstanding aspect of his death is how he was killed for a moment of foolishly NOT being armored.

(Richard Harris as King Richard in Robin and Marian)

I took a lot of inspiration from John Gillingham’s excellent and comprehensive article, "The Unromantic Death of Richard I" that analyzes the different historical accounts that depict his death, and evaluates them based on their closeness in proximity to the event. Some, like William the Breton, King Philip II’s Chronicler, are expectedly critical and biased against Richard, others create a cautionary romantic narrative of a great man blinded by greed and ambition. Most of the dramatic and romantic stories include an element of Richard pursuing buried treasure that he perceives the Viscount of Limoges is keeping from him. However, the Account of Ralph of Coggeshall, generally agreed to be the most accurate account of the death and the circumstances around it, only mentions it as a rumor, not as fact.

Gillingham argues that Richard had political and practical motivations that led him to campaign in Châlus, since the area had already been a contentious one even in the days before he was king, and continued to be so after his death. Because of this, he suggests that both the chroniclers of the day, like Roger of Howden, and even modern historians like Maurice Powicke, have “romantic hearts” that affect how they tell and analyze the story. As a historical enthusiast who enjoys factual analysis, I find Gillingham’s arguments solid and convincing. As an artist, I think there is something to be said about why Richard, as a larger than life figure, lends himself so well to such romantic narratives.

For my comic, I ended up trying to stick fairly closely to the “factual” account. I did not include the buried treasure narrative, and I left out the element about forgiving the killer, or even mention of his identity at all. I even left out the very juicy rumor about Richard not taking his communion “out of his hatred for the King of France.” While it was tempting for the kind of story I was doing, and was a rumor that existed, it kind of stretched my suspension of disbelief a little too much–it felt too Medieval National Enquirer for me. In my depiction of Richard, I wanted portray him as fat–something I’ve also never seen depicted in any media, but a description that is mentioned at the time of his death (listed by a complaint by the doctors tending his wound). It’s one of the rare physical descriptions we have of him, and I wanted to incorporate it.

Obviously, I delve some more into the fantasy aspects and take my liberties, which is the fun part about this sort of project. Here i’ll just list some of my thoughts on the different elements.

- For Richard waking in the hall of the caskets; I was sort of influenced by some of the spooky art of comics like those of Mike Mignola, or the description of the barrow-wights in The Fellowship of the Ring. They appear only briefly but I thought it would be a great way to introduce a creepier and more dream-like vibe, and continue that theme of mortality.

- The female figure is Melusine, the demoness and twin-tailed mermaid and ancestress of the Counts of Anjou. I drew her with a spinning staff and spindle since well, I felt it made sense for her to be holding something in her hands. I think it may have made things a little cluttered, but it felt like something that would exist in a medieval illustration, so I wanted to include it. In the story it’s a bit undefined who she is, which is something I wish I could have made a little clearer, but I hope that at least feeling she evokes, of some strangeness and otherworldliness, still can come across through the art.

- The place that Richard and Melusine reside is a bit ambiguous; I was thinking about different definitions and descriptions of Purgatory, since it’s neither a heaven nor entirely a Hell. Purgatory theology was not codified by this time in the 12th century, but I was influenced by the idea of “flames” either having the connotation of hell, or having the connotation of purification.

Basically, I ended up coming around to making a romantic-hearted moral type of story around Richard's death,, although the moral is less about greed for treasure and more about grudges. And this is where I get into the Yaoi part of it all.

Angevin Yaoiz, Romantic Hearts

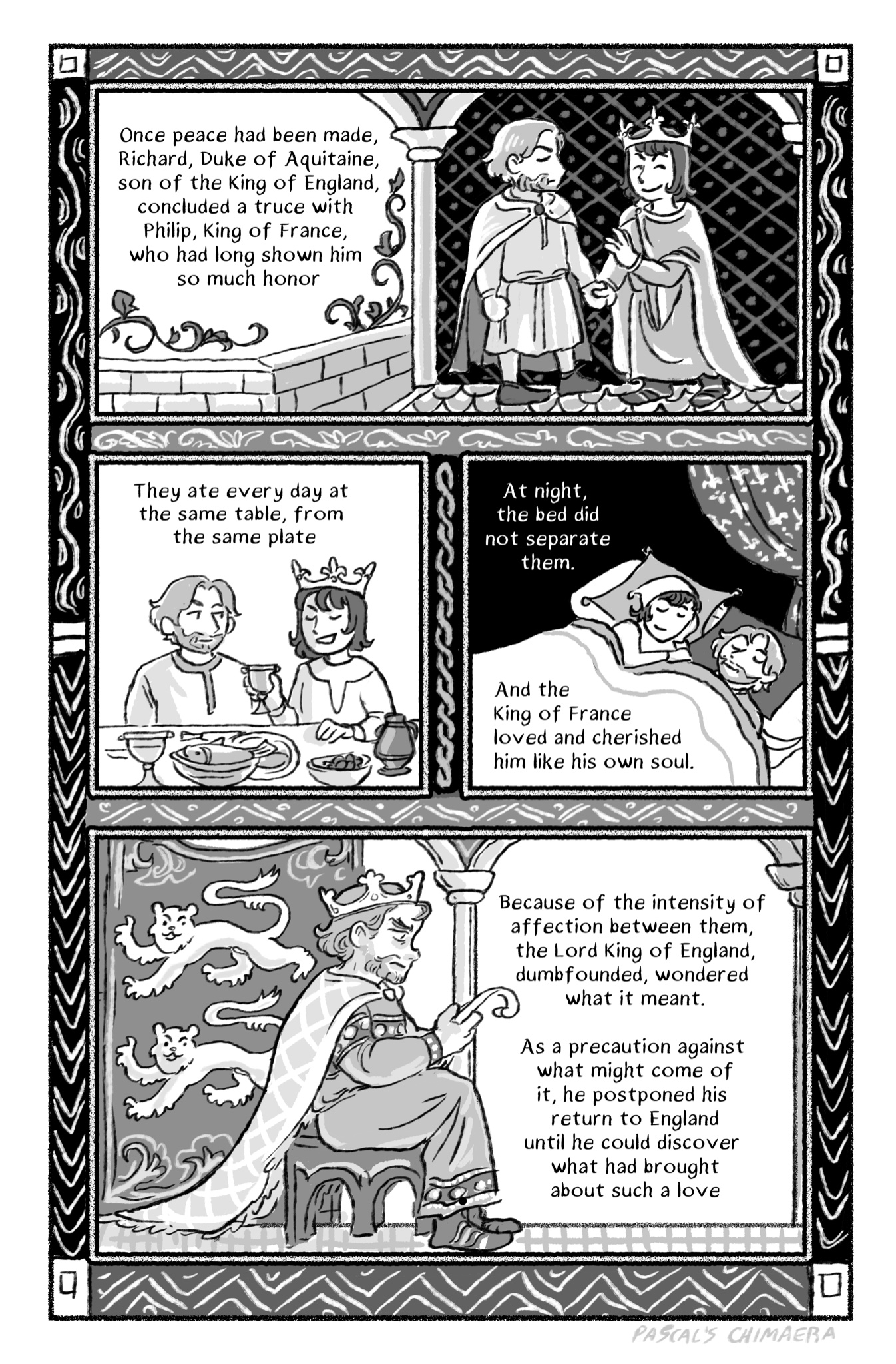

Originally, I was not going to include any real Richard/Philip romantic shipping stuff because I wanted to focus on the other elements, and kind of look at the historical events from a more “objective” point of view.. As I’ve mentioned before, I try to separate my shipping constructions from my historical analysis. Not because I think it’s bad, but because I like to nurture my shipping a little more independently, coming up with headcanons that are completely my own and become less attached to specific historical elements, even as I research to find more inspiration. However, as I worked on the comic, and as I researched a bit more, I realized I could incorporate it into the story as well in a natural way.

The inspiration came from this line from Gillingham’s article, summarizing part of William the Breton’s account in his Philippidos:

At this point the Fates intervened. Two of the old sisters continued to spin the thread of Richard's life, but the third, Atropos, decided that it was time to cut it short. Into her mouth William places a 31-line speech explaining why Richard no longer deserved to live. He is greedy, has no respect for God and holy days, breaks treaties made with his lord, and offends against the law of nature. [emphasis mine]

While I couldn’t find the original text of this speech, I found this very succinct and intriguing. The inclusion of these mythological figures deciding the fate of Richard’s life was similar to my idea of him encountering an afterlife-Melusine, and the list of the grievances, written by his enemies on the French side, felt like an interesting insight.

I decided to add the Philip section to sort of give another perspective to the story. The first few pages have Richard ranting about his grudges and sense of abandonment, so it felt only fair to show the other side. Philip himself was no stranger to complaining about Richard, and being perceived as being envious because of it. Here I will also list some of the things from these few pages I wanted to just mention:

- The Battle of Frèteval was less a battle and more an intense chase where Richard and his forces chased Philip and his army through the woods and forced them to retreat, so hastily that Philip ended up leaving behind his baggage train that included a vast amount of administrative and financial documents. This embarrassing disaster was the impetus for the creation of a centralized library and archive in Paris, which is what he was probably going to chatter on about before being interrupted.

- The Queen here is Agnes of Merania, Philip’s third “wife” who he took after imprisoning his second one. He was in a long battle with the church over her legitimacy and the legitimacy of her children, a battle he eventually lost. However, Agnes seems to be someone he was genuinely attached to for the time they were together.

- He did get permanently bald after catching arnaldia on the third crusade. I like to think this is just another one of his long grievances against Richard that is unrecorded.

To return to the earlier quoted passage, I was very curious about the inclusion of the “offends against the law of nature” line mentioned. I don’t have access to the original text translation, so I just had to work off my own imagination with that one. I thought it was interesting in light of more modern romantic narratives about Richard, namely the ones that find motivations for his actions due to his sexuality. The idea of Richard and Philip being gay for each other due to their bed sharing and early alliance seems to date back to 1948, and Gillingham himself, as well as other current historians criticize the arguments made at the time. Without getting too much Into It, current scholarship also is not in favor of this interpretation of their relationship, although evaluations of Richard’s specific sexuality and sexual activities have varied opinions. Gillingham admits it is not really verifiable, while Jean Flori argues in his book Richard the Lionheart King and Knight that there is an argument to be made of some kind of “equal opportunity lecher” bisexuality.

With this argument being treaded and retreaded (at some point I want to write up a longer article going over the things people have said and argued), I will say that I am not sure what “offends against the law of nature” is supposed to refer to. Gillingham clearly doesn’t believe it refers to sexuality; I personally think it may refer to his crimes of rebelling against his father. During the 1174 rebellion of Henry II’s sons, Jordan Fantosme famously referred to the rebellion as “against nature” in his Chronicle, with other similarly loaded language. That being said, in a modern sense people tend to associate discussions of “nature” and “against nature” with queerness, and I thought it would be fun to play with that linguistic anachronism in my comic here, even if just a little bit.

Philip ended up outliving his enemy by another couple decades, and indeed was able to overtake the lands in western Europe from the much less militarily skilled King John. When Melusine says the lands will be “gambled and washed away,” I was thinking of the Battle of Bouvines in 1214. Battles were avoided in the 12th century specifically because they were gambles–the preferred manner of war was raiding and sieging. Philip may not have been as romantic or charismatic a figure as Richard, but in the end he did achieve everything he wanted. I do like to think Philip would have had some complex feelings about Richard dying; while they were bitter enemies and had fundamentally incompatible political and personal goals, they were very significant in each others’ lives, and at one point were close. It’s impossible, I feel, to work for a long time with someone in various capacities without having more complicated feelings about them as a person, for better or worse.

Having a close relationship does not necessarily signify a sexual or romantic intimacy, but it does lend an interesting framing to the relationship and the ways in which we talk about intense relationships cleaving of any kind usually ends up using the language of romance. For Richard and Philip, the ways in which their political fallout always feels very intense and very personal in the hurt and betrayal described; I think it is not unlike the way people tend to talk about their ex-lovers. Memories that may have been positive become tainted by later betrayals; thoughtless actions gain new significance and are framed as evil. To me, the basis of the “ship” is actually less defined by the brief period of loving relationship and more by the intensity and entwinedness of the hate that came later. All this can be viewed through a political and practical lens, like how Gillingham prudently does. But there is much material to work with for those of us with romantic hearts.

[Back to "The Holy Cephalophore"]Download Digital Zine (free!)